Swiping to find airstrips in Papua New Guinea

What would you do in the middle of the jungle in Papua New Guinea if you had an injured youngster with a fever, no doctor in the community, no pharmacy within walking distance, and no suitable medical supplies either? Use traditional medicine, pray, hope that they will get better eventually, ask for help to come from the sky...

Many settlements on the islands of Papua New Guinea are in areas so remote that there is no road and limited to no connections between communities. As a matter of fact, the only access to health may be via aid organizations using rural airstrips. Around eight million Papua New Guineans rely on rural airstrips (2024), according to the Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF). However, owing to the challenges of economic sustainability in rural regions, many of those airstrips have become defunct.

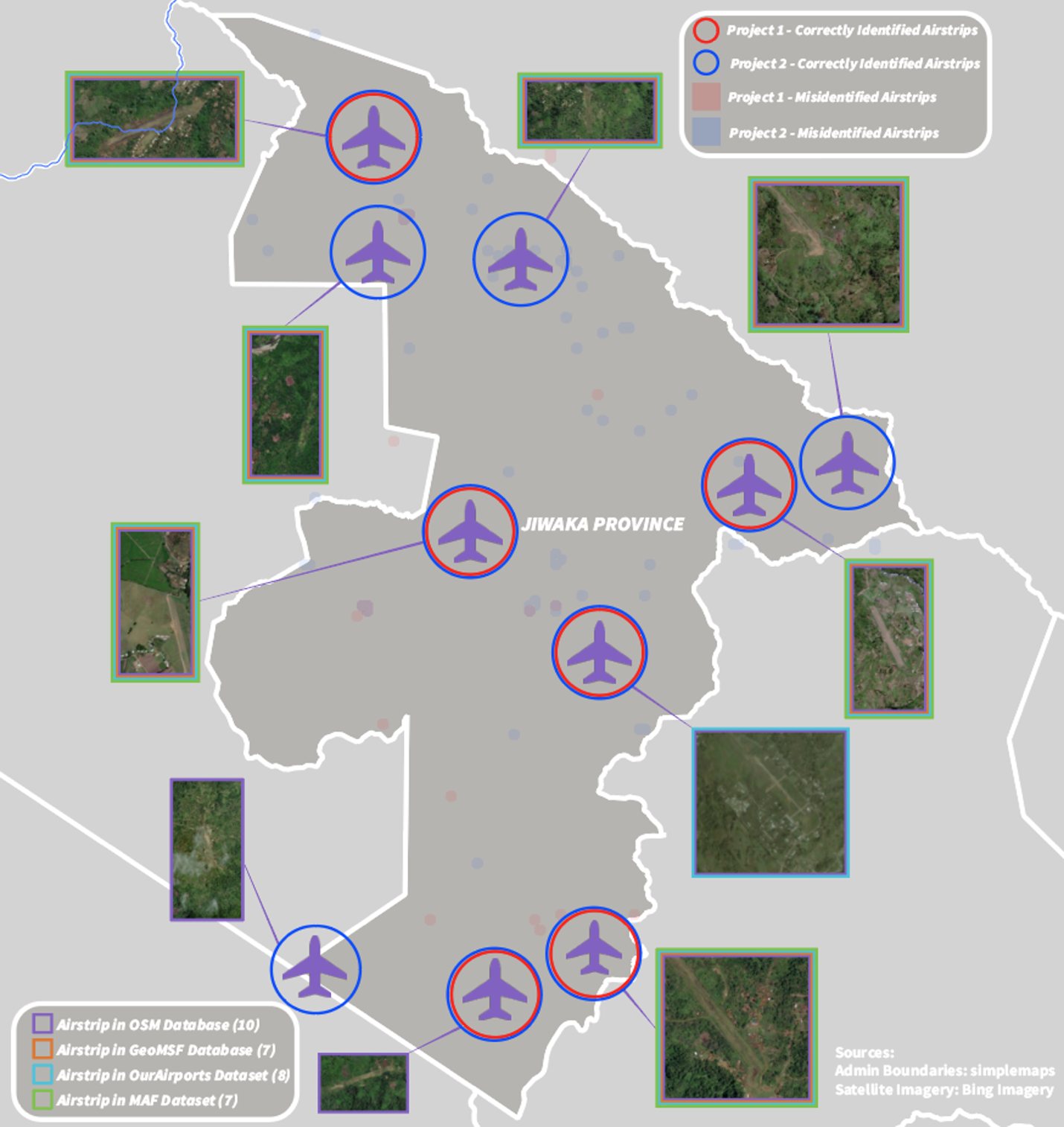

Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), a humanitarian medical organization and a founding member of the Missing Maps project, uses small airstrips to deliver supplies and personnel to remote regions. For MSF, it is thus essential to know whether there are existing airstrips and where they are located. In a MapSwipe project, MSF asked volunteers to identify rural airstrips in the Jiwaka province, where aid can be delivered to and from.

Inputs for Mapswipe to get airstrips as outputs

The first MapSwipe project covering the extent of Jiwaka Province (4,864 km2) was released on June 14, 2024. Since this was the first time MapSwipe was used to identify airstrips, a new tutorial was created by MSF’s Missing Maps team. Examples were shown of easily identifiable airstrips, moderately identifiable airstrips, rivers, towns, and cloud-covered tiles of imagery. Each imagery tile on MapSwipe was shown to three different contributors before it was considered completed. This number is referred to as 'Validation Size'. On the mobile app, 52 users contributed, and completed the project within one day. They swiped on high-resolution Bing Imagery at Zoom Level 16, producing this data, accessible on the MapSwipe website: Airstrips in Jiwaka Province (1) .

Volunteers marked tiles as "yes" (green) or "maybe" (yellow) 21 times, which were subsequently classified via visual interpretation by two MSF staff members as:

- Airstrip: 6

- Potential airstrip: 1

- Forestry: 9

- Farmland: 3

- River: 1

- Cloud covered: 1

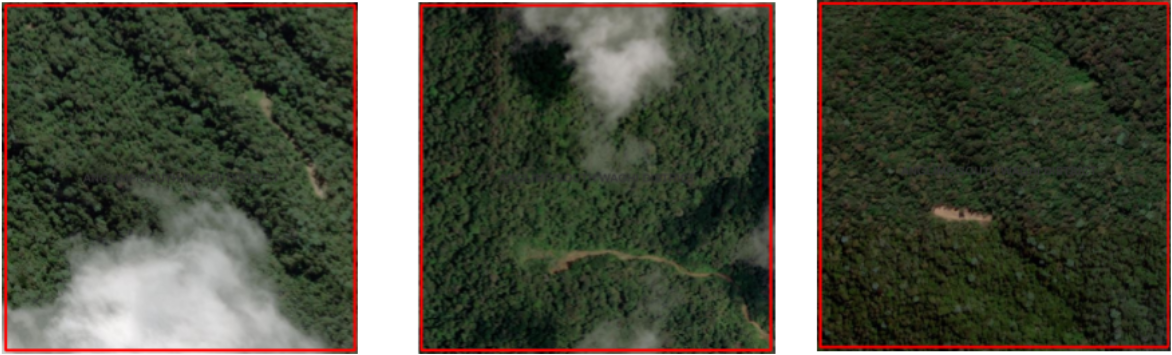

The contributors seemed to be confused with other features, misidentifying forested land, farmland, and cloud-covered areas as airstrips.

The study compared the findings from the Mapswipe dataset against four different data sources: OpenStreetMap (OSM), MAF in Papua New Guinea database, OurAirports, and an internal MSF database. From analysing these datasets, it could be concluded that there are a total of 11 unique airstrips in Jiwaka Province. OSM was the most comprehensive dataset and contained 10 out of 11 airstrips.

Adapting the validation size to increase the number of contributors seeing each tile to five helped to improve accuracy. In the second project iteration, the contributors managed to detect all 11 airstrips within Jiwaka province, including four airstrips that were missed in the first project. The results of Project 2 are accessible on the MapSwipe website here: Find - Airstrips in Jiwaka Province (2) | MapSwipe

The one airstrip identified that was still missing from OSM was added to OSM via JOSM.

There is one caveat: in Project 2, one airstrip was missed, the Kombaku airstrip that lies outside of the Jiwaka Province but was included within the MapSwipe geometries. Taking this airstrip into account as well, the MapSwipe contributors found 11 out of 12 airstrips, which is 91.7% of the airstrips in the area studied.

Taking clearings or roads for small airstrips

In both projects, MSF faced limitations due to satellite imagery:

- The satellite imagery available for the projects consisted of a mosaic of different images, each taken on its own date. Retrieving the exact dates of every piece of imagery is not easy, and they do not match like perfect puzzle pieces.

- Because of the humid climate in Papua New Guinea, a lot of areas are covered by clouds. Some regions, such as Tabibuga, are rarely cloud-free. Hence, cloud-free satellite imagery was not available for use in the MapSwipe projects, which made remote analysis of the airstrips difficult. The ‘latest’ imagery in some regions dated back to more than 12 years ago.

Most Mapswipe projects focus on identifying or validating buildings. This type of map feature was likely new to most MapSwipe contributors. Even though the tutorial for the projects integrated different examples to distinguish various classes of land use from airstrips, the MapSwipe contributors still identified forested land or river features as airstrips. The confusion could have arisen from roads, tracks, or clearings standing out from the forest background. More examples of forested land with roads that are distinctly different colours would possibly help in the tutorial. Even though an example of a river was included in the tutorial, it still was detected by MapSwipe contributors as an airstrip, so a solitary previous example does not necessarily ensure a correct visual interpretation.

Why mapping matters for health

People in the Jiwaka province suffer from many types of violence, including election-related, inter-community, domestic, sexual and gender-based violence, and repercussions due to accusations of sorcery. In Spring 2024, MSF wanted to start a new project in the province to aid survivors of tribal and sexual and gender-based violence. As part of an initial exploration, the field team noted that there were no maps for some of the areas. This led to a GIS Adviser asking for a Missing Maps campaign. Soon, it was launched to help map basic features, enlisting volunteers. For example, in February 2024, volunteers from the Czech and Slovak Missing Maps community mapped shelters at a hybrid mapathon in Prague with support from international validators.

In June 2024, the MSF teams began working on a community-based approach to healthcare by strengthening the capacity of existing medical services, and this Mapswipe analysis was launched. The location of all airstrips is vital to ensuring that survivors of violence in the Jiwaka Province can have access to health.

Applicability

With five persons interpreting each square of imagery instead of three, there was a substantial increase in the detection of airstrips within the Jiwaka Province, from 64% in Project 1 to 100% in Project 2. The outputs of the second Mapswipe iteration successfully identified all of the airstrips within the area of interest (if not counting the missed airstrip in Kombaku). However, Project 2 also showeda notable rise in false positives, but they were welcomed as part of the exercise. The additional work of manually reviewing those extra tiles does not outweigh the potential impact of missed airstrips – that help cannot come from the sky. We concluded that MapSwipe, with the validation size set to five, was a worthwhile tool to detect airstrips.

The MSF Missing Maps team has already received interest in using the above-mentioned workflow and various questions about it, which was one of the reasons for producing this blog. If you have any comments, Nash and the team will be happy to hear from you; you can contact us via info@mapswipe.org.